Cyber attacks involving malware have gotten a lot of attention lately.

If you’re not familiar, malware is software intentionally designed to harm a computer, like a virus. It is often spread through phishing emails or via websites that have been infected. Ransomware is a type of malware that encrypts (i.e locks) all the files on the infected device. To obtain the decryption key and unlock the files, the software requires payment of a ransom. Hence the name, ransomware.

Most ransomware requires payment in bitcoin, the most accessible and liquid cryptocurrency.

There have been several high profile ransomware attacks this year against major US companies. The most recent was against Colonial Pipeline, which provides roughly 45% of the fuel for the East Coast. In May, Colonial’s computer systems were held hostage by a cyberattack, and the CEO decided to pay the $4.4M bitcoin ransom to regain control of their systems.

Six years ago, I helped a software company in the same situation.

This is that story.

May 2015

I received a phone call from one of my childhood neighbors. She was an accomplished banking attorney in Oklahoma and one of the smartest people I know. She was aware I represented cryptocurrency companies and had invited me to speak about Bitcoin at a few community banking events.

My neighbor was friends with an executive at a software company in Oklahoma City. The executive had called her the day before because two of the company’s computers had been infected with ransomware.

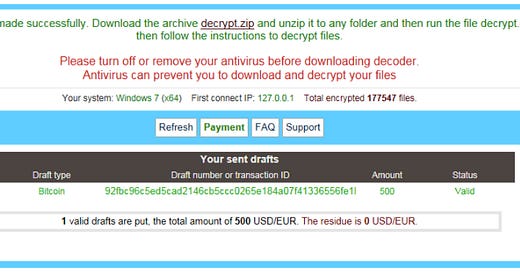

The particular brand of ransomware that had infected the company’s computers was requesting a USD$500 payment in bitcoin. The price of bitcoin then was roughly $250.

A screenshot of the pop up window on the infected computers is below.

If you are a victim of ransomware, you have to make a decision. Is it cheaper to pay the ransom or replace the infected computers? In our case, the company determined it was cheaper to pay the ransom. The ransom was $500, and new computers would cost $1000/ea. Simple math.

One small problem…they didn’t have any bitcoin.

These were thoughtful hackers, who understood their target market. They correctly assumed most of their victims wouldn’t have bitcoin lying around for a ransom. So they very conveniently included instructions on how to purchase bitcoin in the pop up window on the infected machines.

Thoughtful hackers.

Side note…today, because the threat of ransomware is very real, some companies have actually preemptively purchased bitcoin in the event they need to pay a ransom. If they never have to, it becomes an investment.

Now, the company could have purchased bitcoin on their own, but that would have required them to set up an account on an exchange (solely for the purchase of paying the ransom, which most exchanges won’t allow), transferring USD onto the exchange, buying the requisite amount of bitcoin, and sending it to the hackers. For someone new to crypto, this was technical and overwhelming.

This is where I come in.

My neighbor arranged a call between me and the software company’s CEO. On the call, he tells me about their situation and asked if I was willing to front the ransom payment if they reimburse me. After a few minutes, I agreed to do it on the condition I would be reimbursed whether they were able to decrypt their files or not.

Worst case scenario…I’ve got a great story.

The Drop

The pop up window on the infected computers contained payment instructions, complete with the desired amount and wallet address to send the bitcoin (see below).

Now, Bitcoin is pseudonymous, so there is no way to connect me or the software company to the payment. So how does the hacker know we sent the money? We have to prove it, by providing the transaction ID for the payment (i.e. a unique identifier).

Movies glamorize ransom payments. Millions of dollars in a duffle bag, dropped off in an obscure location late at night.

Not me. The next day, I was at my desk…eating lunch (likely a PB&J and flaming hot cheetos….don’t judge…I was in my 20s).

I got on a conference call with the CEO of the software company and transferred 2.08 BTC to the specified address. Once the payment was made, I emailed the Transaction ID to the company. They copied and pasted the transaction ID from my email into the blank field on the screen, and pressed “Pay”.

The whole process took 10 minutes.

Now we wait.

I hung up the phone and went back to work. 15 minutes later, the following message appeared on the infected computer’s screen, with a link to a decryption file that would unlock the computers.

Later that afternoon, the company called to tell me they had successfully decrypted the files on their computers, and that my $500 check was in the mail.

My job was done.

Follow the Money

Now that could have been the end of the story, but I was invested in this.

Where did my 2.08 BTC go?

Fortunately, blockchain transactions are public. We could literally follow the money.

I reached out to a friend at Chainalysis, the largest blockchain forensics software company, and asked if he would run a diagnostic on our ransom payment.

The next day, he sent me this diagram:

If you don’t know what you’re looking at, let me break it down.

This is a funds flow diagram, showing how crypto moves from one wallet to another. The circles are wallets, and the arrows show the direction of the flows. The “Ransom Cluster” is a group of addresses used by the hackers (70 addresses in total). As far as we could tell, they would use the same address no more than twice.

If you look at the bottom left, you can see the Ransom Cluster received 266.9198 BTC over 133 transactions, presumably all ransom payments. 266.9198/133 = 2.006 BTC/transaction. The average transaction amount is pretty consistent with the 2.08 BTC ransom amount we paid.

Looking at the diagram, you can see that most of the BTC in the Ransom Cluster had been transferred to the “1Chr6” address.

Here’s where it gets interesting.

The “1Chr6” address also received transfers from the “1GQrK” address (the red circle), which has received transfers from accounts at two exchanges, Bitstamp and Circle.

Now, when you’re trying to figure out who was involved, interactions with reputable exchanges can prove useful. When you set up an account at the exchange, you have to provide personal information (name, address, email, driver’s license, etc.). Could these account holders be the hackers? Maybe. But even if they aren’t, it’s a start.

While I didn’t have enough information to identify the hackers, there were enough breadcrumbs to justify further investigation.

I compiled the ransom instructions, payment details and forensic analysis and sent it to the FBI field office in Oklahoma City.

I’m not sure if the FBI ever investigated further. The reality was in 2015, cryptocurrency and ransomware were not as well understood and very few resources in law enforcement had the knowledge to investigate these cases. The dollar amounts in question also weren’t large enough to attract the spotlight.

Parting Thoughts

266 BTC at today’s prices would be worth approximately $9.5M. I’m confident that would have gotten the FBI’s attention.

In the year’s since, law enforcement has become more sophisticated, and the forensics tools have improved.

Last month, special agents from the FBI were able to track Colonial Pipeline’s ransom payment the same way I did, and recovered $2.3M, roughly half of the ransom.

Thanks for reading,

Andy

--

Not a subscriber? Sign up below to receive a new issue every Sunday.

great story! Thanks for sharing